Case

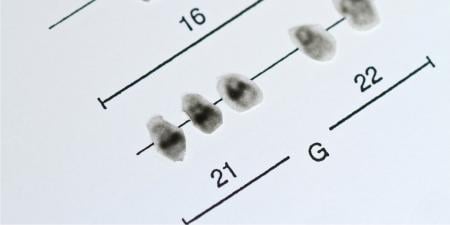

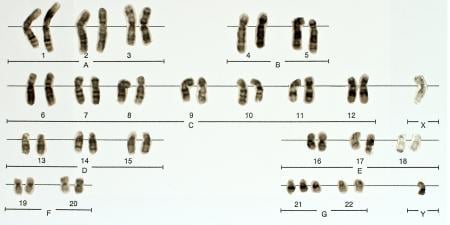

Mr. Jones, a 49-year-old accountant, visited Dr. Seelinn, a urologist, for the first time. Mr. Jones's sister had been treated for ovarian cancer and his mother had a history of breast cancer. While his sister was receiving treatment for her cancer, her physician recommended that the entire family be screened for breast cancer 1 and 2 (BRCA1 and 2) mutations, and Mr. Jones agreed to have this test.

Several weeks after the test, Mr. Jones learned that he tested positive for a mutation and was sent a form letter stating that "men with this mutation have a 6 percent chance of developing breast cancer and a 7 percent chance of developing prostate cancer before age 70." Concerned about his results, he went to see Dr. Seelinn to find out what he should do with this new information. As he handed Dr. Seelinn the letter, Mr. Jones laughed and said, "If I had known the test wasn't going to give me a definite yes or no answer about whether I was going to get cancer, I wouldn't have had it. I don't know anything more than I did before the test."

Dr. Seelinn is also unclear about what this reported risk of prostate cancer means. Does it mean biopsy-proven prostate cancer (which may be unlikely to progress if diagnosed in his late 60s)? Or does it refer to the risk of advanced prostate cancer that would present with symptoms? He's not even sure if this letter means that Mr. Jones is at a higher or lower risk of prostate cancer than men without the mutation.

Seeking to provide Mr. Jones with some guidance and more information, Dr. Seelinn performed a urologic history and a thorough physical exam, including a breast exam and a digital rectal exam (DRE) of the prostate. All of these were normal. Dr. Seelinn also ordered a prostate-specific antigen test (PSA) even though he didn't expect to find anything abnormal in the results.

After Mr. Jones left, Dr. Seelinn wondered whether finding out about his genetic alteration held any benefit for Mr. Jones. Did Mr. Jones really understand what a positive test result would mean? Furthermore, what follow-up schedule is appropriate for Mr. Jones, who appears to be a healthy, 49-year-old man?

Commentary 1

Though Socrates claimed that knowledge is good and ignorance, evil, this case shows that a little bit of knowledge may be worse than none at all. The problems began when Mr. Jones's sister's physician (let's call her Dr. Protest) encouraged Jones and his siblings to be screened for the BRCA1 and 2 genetic mutations. The encouragement came without counseling (or even an offer to counsel) Jones and his siblings about the outcomes of the test and the various risks and benefits of knowing whether one has the mutations. Instead, by making a blanket recommendation for the screening, Dr. Protest led the Jones family to believe that taking the test would be good for them. After all, why else would their sister's trusted physician have recommended it, Mr. Jones is likely to have reasoned. So he signed the paperwork for the test believing, among other things, that it would give him a definitive answer as to whether he would get cancer like his sister and mother. If the test were positive, then he could vigilantly watch for the first signs of cancer and start treatment early enough to be cured. If the test were negative, he'd be safe from the disease and free from that worry. However, because BRCA1 and 2 testing will tell him nothing of the sort, it is clear that Jones did not understand what he was doing and thus could not have given truly informed consent to the testing.

The preceding problem of consent would have been minimized had Dr. Protest properly counseled Jones about the outcomes, risks, and benefits of BRCA1 and 2 screening. Alternatively, Dr. Protest could have merely recommended that Jones speak to his own physician about the possibility of testing and its risks and benefits. As an additional safeguard, the lab that conducted the test might have offered Jones a brochure explaining what the testing would and would not show and asked Jones to read the brochure before signing his consent form.

Of course, neither option would guarantee that Jones truly understood what the test could and couldn't do for him. His fear of cancer, heightened by having both his sister and mother suffer from it, coupled with society's general presumption that screening is beneficial, might have created in Jones an irrationally optimistic presumption about the benefits of BRCA1 and 2 screening that standard counseling and a printed brochure would not have overcome. That is, there is a fairly widespread belief in our society that screening is good for people. The incorrect assumption is that simply finding a cancer earlier is worthwhile when in fact screening is only beneficial if it lowers the morbidity or mortality from the disease without causing undue harm. For diseases such as prostate cancer, for example, there is currently no good scientific evidence that morbidity or mortality is affected by screening, hence the inadvisability of strongly recommending routine screening. Still, the counseling and brochure would have gone a long way toward meeting the objective of informing Jones sufficiently to consent to or decline testing, and the counseling itself is a minimum standard that should be met by any physician who recommends a screening test.

But the absence of true informed consent isn't the only problem in the case. Even if Mr. Jones had understood that the genetic testing would only tell him about his statistical risk of getting cancer, the information provided in the form letter response was too cryptic to be of any use and therefore was not beneficial. Did the stated 7 percent chance of developing prostate cancer by the age of 70 mean the chance of developing microscopic autopsy-proven prostate cancer? Or was it a risk of developing potentially aggressive cancer eventually leading to symptoms that would affect Jones's quality of life and possibly his survival? And how does either alternative compare with men who lack the mutation? An answer to this last question is needed in order to determine whether the information gained from the genetic screening will make any meaningful difference to future nongenetic screening—eg, PSA, DRE—and treatment recommendations.

Suppose that the 7 percent risk referred to the first alternative, Jones's risk of developing biopsy-proven but non-life-threatening prostate cancer. In this case, Jones would seem to be at a lower risk than similarly aged men who lack the genetic mutation. Autopsy studies have shown that by age 50, approximately 30 percent of all men in the United States have microscopic evidence of prostate cancer, and that this percentage increases to 50 percent by age 80 [1]. Yet the annual mortality rate for this type of cancer is quite low. Thus, given that the majority of these cancers do not progress to the point of adversely affecting the person's life, it isn't clear that learning one is at a comparatively low risk of developing such a cancer is a benefit. Alternatively, suppose the 7 percent refers to Mr. Jones's risk of developing potentially aggressive prostate cancer sometime in the future. It still isn't clear where this places him in comparison to other men and thus whether it has any bearing on future screening and treatment decisions. A 7 percent risk of developing prostate cancer before the age of 70 is not the same thing as a 7 percent risk of dying from it: most men with prostate cancer die with the disease and not from it. Further, if the vigilant search for this potentially aggressive cancer leads to the detection and treatment of the much more statistically likely microscopic cancer that would never progress to the point of adversely affecting Jones's life, then the information may even have made him worse off. In either case, it seems that the information contained in Mr. Jones's form letter response did not provide a meaningful benefit.

Furthermore, the minimal information in Mr. Jones's form letter led Dr. Seelinn to conduct and order other exams and tests, ostensibly to provide Mr. Jones with the guidance and information lacking in the letter. But this introduces a new version of the first problem. Dr. Seelinn ordered these tests and exams without talking to Jones about their various risks and benefits. Thus Jones was once again denied the opportunity to give true informed consent. In particular, Dr. Seelinn ordered a PSA test without telling Jones that the benefits and even usefulness of the test were controversial. To date, no study has proven that asymptomatic men such as Jones live longer if testing is performed, yet the harms of treatments performed in response to suspicious results and diagnosed cancers include impotence and incontinence as known possible side effects. Further, data from a recent study showed that no PSA value can be considered normal, in the sense that some men with the lowest PSA levels will have a positive biopsy for cancer [2]. Therefore, a major goal of PSA screening—definitively informing the patient that he does not have the disease—is not currently possible. Had Mr. Jones been told these and other relevant facts, it is at least possible that he would have declined the screening. But he wasn't given that option. And he was told nothing about the breast cancer screening at all.

Perhaps Dr. Seelinn thought that the additional testing was necessary to protect himself from future legal liability. That is, it might be argued that, given our overly litigious society, Dr. Seelinn would risk being successfully sued if he failed to order the PSA screen now and Jones were later found to have prostate cancer. But this argument is faulty in a number of ways. First, the argument assumes that Jones would have been better off finding a cancer now rather than later. But that assumption is controversial at best, as discussed above. Second, the question isn't whether Jones should or shouldn't have a PSA test, but whether Jones was given the information and opportunity to decide for himself whether he wanted the test based on known facts about the limitations of screening. Third, Dr. Seelinn can limit his medical-legal liability by properly documenting that he did in fact inform Jones of his options and the various risks and benefits and then let Jones decide for himself. Finally, even if a recommendation for screening has become part of the established standard of care in Dr. Seelinn's community, the related legal doctrines of the respectable minority and 2 schools of medical thought would protect Dr. Seelinn's decision to not recommend the test, as long as he informed Mr. Jones of its availability. The details of these doctrines vary among jurisdictions, but each generally serves to protect from malpractice liability physicians who elect to pursue one of several recognized courses of treatment, even if the elected course is not preferred by the majority. As one court stated, "where two or more schools of thought exist among competent members of the medical profession concerning proper medical treatment for a given ailment, each of which is supported by responsible medical authority, it is not malpractice to be among the minority in a given city who follow one of the accepted schools" [3].

In summary, the case at hand involves a series of missed opportunities for clear communication and thus for true informed consent. Jones acted on the first recommendation without knowing what it could and couldn't do for him, and the problems snowballed from there. Such an approach is unlikely to lead to optimal patient care.

References

- Sakr WA, Grignon DJ, Crissman JD, et al. High grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HGPIN) and prostatic adenocarcinoma between the ages of 20-69: an autopsy study of 249 cases. In Vivo. 1994;8(3):439-443.

- Thompson IM, Pauler DK, Goodman PJ, et al. Prevalence of prostate cancer among men with the prostate-specific antigen level < or = 4.0 ng per milliliter. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(22):2239-2246.

-

Chumbler v McClure, 505 F.2d 489 (6th Cir 1974).