Case

Andy was admitted to Shady Grove Hospital with a pneumonia that progressed to an empyema. He was assigned to the teaching service with Dr. Lee attending, along with a second-year resident, Dr. Weiss. Dr. Weiss did an initial interview and recorded her history and physical in the chart. She presented her findings to Dr. Lee and they agreed upon a plan to have the empyema drained and antibiotics started.

The following day, Dr. Krause, a physician colleague of Dr. Lee's approached him to express some concerns. She had been on call the night before and was asked a question about Andy's care. Upon reviewing his chart she noted the sexual history that was documented by Dr. Weiss. Dr. Weiss' full sexual history included documentation that Andy was a homosexual, became sexually active about a year earlier at age 15, and "mostly" used condoms. The history also noted that Andy had several sexual partners in the last year and documented his typical sexual practices. Dr. Krause told Dr. Lee that she felt that the history was too graphic and was inappropriate for inclusion in the chart. She explained that she felt obligated to refer this case to the hospital ethics board and was going to do so.

Dr. Lee reviewed the chart. He and Dr. Weiss had discussed the patient's sexual history, and, based on his risk factors and his disease presentation, they had already decided to order additional testing, including an HIV test.

A few days later Andy was recovering well after drainage of his empyema. He was feeling better and was excited to go home soon. In checking his morning lab results, Dr. Weiss noted that Andy's HIV test had come back positive. Dr. Weiss and Dr. Lee counseled Andy about this result, arranged for the HIV clinic coordinator to see him, and began to plan his outpatient follow-up. The following week Andy was discharged. Because of the complaint lodged by Dr. Krause in regard to the medical records, Drs Lee and Weiss were asked to sit before the hospital ethics board.

Commentary 2

Dr. Weiss should be commended for making Andy feel comfortable enough to disclose his sexual history. It is difficult for many clinicians to elicit information about sexual practices and risk behaviors from an adolescent—straight or gay. It is the clinician's responsibility, however, to gather detailed information during the interview process in order to identify risk behaviors and to ensure that a proper diagnosis is made and that the patient receives the best possible care and counseling. Had Dr. Weiss not completed a full sexual history, the presenting problem alone may not have led to the diagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). This would have been a disservice not only to Andy but also to his past, present, and future sexual partners.

A Comprehensive Sexual History

A comprehensive sexual history is a vital part of the medical evaluation of all adolescents. The clinician should ask questions in a nonjudgmental manner, beginning with less personal questions and progressing to more sensitive areas.1 In addition to Dr. Weiss' questions (sexual orientation, age of onset of sexual intercourse, condom use, number of sexual partners, and typical sexual practices), a complete sexual risk history should include age of partner(s); sexually transmitted infection (STI) history including symptoms, treatment, and prevention measures; partner's risk factors for STIs; drug or alcohol use before or during sex; history of sex in exchange for food, money, drugs, or a place to sleep or live; and history of sexual abuse or negative sexual experiences.2 These details are necessary to assess the patient's risk of HIV infection, and their relevance has been corroborated by multiple studies, which showed that:

1. Adolescents who have unprotected intercourse, especially those who begin at younger ages, with multiple and older partners, or in geographic areas with a high HIV seroprevalence are at greater risk for HIV infection.3

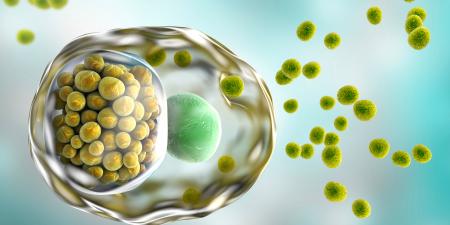

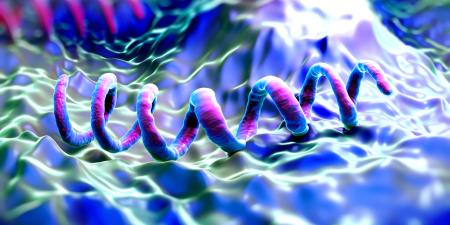

2. STIs are highly correlated with and predictive of HIV infection, leading some researchers to use STIs as a surrogate marker for behaviors associated with HIV infection. Certain STIs may also increase susceptibility to HIV infection, particularly those associated with genital ulcers, which provide easy access to HIV entry through the compromised skin barrier. The increased incidence of syphilis and chancroid parallel the rise in HIV rates.3

3. Certain types of sexual practices are associated with a greater risk of HIV transmission. For example, receptive anal intercourse may be a more efficient means of transmission than vaginal intercourse, which in turn may be more efficient than oral intercourse.3

4. For sexually active persons, condoms are the only form of protection against HIV infection, yet a national survey of 17-to-19-year-old males revealed that only 3 out of 5 in this age group had used them the last time they had intercourse. Condom use was lowest among males who reported 5 or more sexual partners or intravenous drug use.4 Another survey conducted among middle-class urban adolescents showed that only 8 percent of males used condoms every time they had intercourse.5 When used properly, latex condoms are an effective barrier against STIs, so adolescents lower their risk for HIV infection if they consistently use condoms during intercourse.3

5. Alcohol and drug use impairs judgment and therefore further increases the probability of unprotected sex.6 Adolescents who use alcohol before intercourse are 2.8 times less likely to use condoms, while those who use marijuana before intercourse are 1.9 times less likely to.7

Sexual Risk Assessment

The primary purposes of the sexual risk assessment are to identify and triage high-risk adolescent youth into appropriate services and to tailor interventions for prevention and risk reduction to the needs of a particular adolescent.3 All information obtained during the sexual history should be documented in the chart regardless of the setting (inpatient and outpatient) so that any future clinicians are fully aware of the patient's risk-related behaviors and can screen, treat, and counsel him or her accordingly.

Special Considerations for Gay and MSM Adolescents

Gathering a detailed sexual history from a male adolescent who has unprotected sex with other males (MSM) is especially crucial because these partners are at particularly high risk for contracting HIV.5 MSMs ages 20 and older represent the largest HIV transmission category.6 In 2003, the CDC estimated that 63 percent of newly diagnosed HIV cases in the US were among MSMs.8 More recent data from 5 of the 17 cities participating in the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance (NHBS) system from July 2004 to April 2005 indicated that 25 percent of the MSMs surveyed were infected with HIV. Forty-eight percent of those who tested positive were unaware of their infection. The proportion of unrecognized HIV infection was highest among MSMs under 30 years of age.9

The stigma associated with homosexuality often drives gay or MSM adolescents to explore their sexuality in "secretive and sometimes unsafe ways."5 Although safe-sex messages aimed at the gay community are ubiquitous, MSM adolescents often do not have access to or ignore the messages because they do not identify themselves as gay.5 For example, in a study of 72 MSMs between the ages of 16 and 25, 69 percent self-identified as gay, while the remainder self-identified as bisexual (14 percent), gay or bisexual (6 percent), ambivalent or exploring (6 percent), transgendered (3 percent), or heterosexual (1 percent). MSMs who did not self-identify as gay reported a lack of acceptance by the gay community. Furthermore, many MSMs of color did not consider themselves gay if their MSM activity was limited to receptive oral sex.10 The discrepancy between sexual orientation and behavior can lead to false assumptions about risk behavior and misguided counseling, so it is imperative that clinicians distinguish between sexual identity and activity.6

Consent and Confidentiality

Although this case does not make specific reference to HIV counseling, testing, and referral, these topics should be addressed. Clinicians should counsel all sexually active adolescents about the significance of HIV testing and offer voluntary testing with informed consent (most states permit minors to give their own consent for STD testing and treatment.)11 The federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) protects patient information from inappropriate disclosure by health care clinicians, insurers, and certain government programs (eg, Medicaid.)12 Many states have additional laws that limit parents' rights to access their children's medical information, but the specifics of such regulations vary from state to state.11 Clinicians should become familiar with HIPAA and the laws of their particular state, as it is their responsibility to ensure that adolescents are fully informed about disclosure requirements. This is vital because the fear of inappropriate disclosure causes many adolescents to avoid or delay needed care.6 For gay youth, this anxiety is compounded by the possibility that they will face homophobic discrimination, loss of close personal relationships, or even banishment from home, upon disclosure of their sexual orientation.6

Pretest Counseling

Before adolescents sign the consent form, clinicians should present to them the advantages and disadvantages of testing and available testing options in "simple, culturally and developmentally appropriate language."6 Adolescents should be encouraged to involve a supportive adult in the testing process. In addition to discussing the test itself, the pretest counseling session gives clinicians the opportunity to talk to adolescents about sexuality, to identify high-risk behaviors, and to devise a personalized risk reduction plan.6,13

Post-Test Counseling

Clinicians should provide results in a straightforward manner, allow plenty of time for the adolescent to respond, validate the response, and then ensure that the adolescent understands the meaning of the results. Other important aspects of post-test counseling include helping adolescents identify support systems and offering assistance in notifying partners and parents. Counselors should emphasize risk reduction behaviors and develop short- and long-term plans to address adolescents' emotional and medical needs such as mental health or drug rehabilitation referrals or both. In addition, clinicians may provide services such as a contact list with phone numbers for emergency mental health services, a 24-hour crisis hotline, and follow-up appointments.6

Conclusion

The sexual risk history is a relevant and indispensable part of the medical interview that aids the clinician in his or her understanding of the patient's risk for HIV infection. The clinician should err on the side of documenting more detail, not less, to aid other clinicians in the continued care and counseling of the patient. Protective measures such as HIPAA ensure patient confidentiality, so the information Dr. Weiss documented in Andy's chart does not present any ethical concerns. Thus, Dr. Krause's referral of Drs Weiss and Lee to the hospital ethics board was inappropriate.

Dr. Weiss's "graphic" sexual history was merited because it led to the discovery that Andy was infected with HIV, a diagnosis that not only shed light on the cause of his current problem but also opened up an opportunity for a public health intervention. As a result of Dr. Weiss's history and diagnosis, Andy may be linked to appropriate continuous care, allowing him to live a healthier life and take measures to prevent further transmission of the virus. The hospital ethics board should therefore dismiss Dr. Krause's complaint. Instead, the board might recommend implementing a workshop aimed at improving clinician's competency in approaching and managing sexual minorities and the importance of eliciting a comprehensive sexual history from all patients.

References

-

Bidwell RJ, Deishre RW. Gay and lesbian youth. In: McAnarney ER, Kreipe RE, Orr DP, Comerci GD, eds. Textbook of Adolescent Medicine. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Company; 1992:234.

-

Futterman DC, Hein K. Medical management of adolescents. In: Pizzo P, Wilfert C, eds. Pediatric AIDS: the Challenge of HIV Infection in Infants, Children and Adolescents. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1990:757-772.

-

Kipke MD, Hein K. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and human immunodeficiency virus-related syndromes. In: McAnarney ER, Kreipe RE, Orr DP, Comerci GD, eds. Textbook of Adolescent Medicine. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Company; 1990:713-714.

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth risk behavior surveillance–US 1993. MMWR. 1995;44:1.

-

Futterman D, Hoffman N, Hein K. HIV infection and AIDS. In: Friedman SB, Fisher MM, Schonberg SK, Alderman EM, eds. Comprehensive Adolescent Health Care. 2nd ed. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby; 1998:565-566.

-

Ryan C, Futterman D. Lesbian and Gay Youth: Care and Counseling. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 1998:34,103,106,113.

- Leigh BC, Stall R. Substance use and risky sexual behavior for exposure to HIV. Am Psychol. 1993;48(10):1035-1045.

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report (15) 2003. Atlanta, Ga: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2004:6. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/stats/2003SurveillanceReport.pdf. Accessed July 16, 2005.

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV prevalence, unrecognized infection, and HIV testing among men who have sex with men—five US cities, June 2004–April 2005. MMWR. 2005;52:597-601.

- Seal DW, Kelly JA, Bloom FR, Stevenson LY, Coley BI, Broyles LA. HIV prevention with young men who have sex with men: what young men themselves say is needed. AIDS Care. 2000;12(1):5-26.

-

Gudeman R. Adolescent confidentiality and privacy under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Youth Law News.2003;3:1-2. Available at: http://www.youthlaw.org/downloads/adolescnt_confidentiality.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2005.

-

US Department of Health and Human Services. Fact sheet: privacy and your health information. HHS Office for Civil Rights Web site. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/hipaa/consumer_summary.pdf. Accessed July 19, 2005.

- Peralta L, Constantine N, Griffin Deeds B, Martin L, Ghalib K. Evaluation of youth preferences for rapid and innovative human immunodeficiency virus antibody tests. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(7):838-843.