Case

Adina and Jessica are third-year medical students on the same team during their medicine rotation. One day at lunch, Jessica begins to tell Adina about her plans to do a global health elective over their summer break. After a year of clerkships, she is excited to travel to Thailand to see the way medicine works in a developing nation. She thinks going abroad will strengthen her residency application and give her an opportunity to practice clinical procedures and skills that she rarely gets a chance to use in the United States.

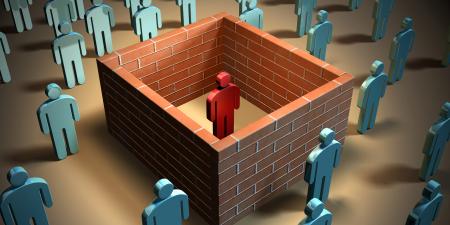

Adina, who was born and grew up in Ethiopia, questions Jessica’s decision to spend her summer visiting hospitals abroad. Adina deplored the programs that sent medical trainees into her home village when she was younger. She explains that many local people felt that the foreign students who came to their village for short periods of time actually placed a burden on the health care system rather than contributing to improving care. She tells Jessica about how her uncle, a pediatrician, met several students who rotated through his hospital. They came into the community, lived in a group apart from the people, and barely interacted at all with the local clinicians. When they were in the hospital, they frequently needed a lot of translating assistance to communicate with patients and figure out what resources were locally available in the hospital or the town. Adina’s uncle was also shocked that foreign students were often allowed to take on tasks above their level of training, although this tended to be viewed by the local people as an opportunity to help the students by allowing them to practice their skills. This took up nursing and support staff time, distracted from the education and training of local clinicians, and further stressed an already resource-strapped system.

The visitors also failed to try to understand the local culture. Adina’s uncle had told her, for example, that the visiting students, used to a time- and appointment-driven system in the United States, got very frustrated and even angry when patients did not show up exactly on time or were annoyed when patients’ families accompanied them to visits, a crucial support system in the culture. The superficial working relationship between the local and foreign students and clinicians was weakened further when the visiting students skipped work to travel or sightsee.

Commentary 1

Jessica and Adina’s conversation highlights the attraction global health electives (GHEs) hold for medical students, medical schools, and host communities. Students request these electives and medical schools and many communities around the world allow them. But who takes responsibility when ethical questions about GHE arise?

Up to thirty percent of American medical school graduates have participated in global health electives [1]. Their motives for participating vary and may include Jessica’s difficult-to-justify goals, such as practicing invasive medical procedures on patients in resource-limited settings [2-6]. However, GHEs are generally encouraged because they expose medical students to the different determinants of health such as socioeconomic status, tropical and other geographically determined diseases, and cultural influences in resource-limited countries, among others [7].

Forty-four percent of Canadian and at least 40 percent of United Kingdom medical students personally choose and arrange a GHE at an elective site with minimal oversight from their medical school [8-10]. Only 30 percent of North American medical schools provide some kind of pre-departure education or counseling for students going on GHEs; all medical schools in the United Kingdom do, but 90 percent of them do not tailor that education to specific destinations [9, 11]. When so many students arrange their electives themselves and the majority of medical schools do not provide adequate preparatory education for GHEs, numerous problems can arise and go unresolved, as noted by Adina and her uncle [12]. These problems include, but are not limited to, unprofessional behavior and unreasonable expectations on the part of student participants, lack of sympathy and trust between program participants and the communities in which they are working, and poor leadership of the programs, leading to inadequately supervised students and injudicious allocation of the local practitioners’ time between teaching and clinical duties. These concerns must be addressed on an individual level, with humility and cultural awareness on the part of each student, and on an organizational level, through the implementation of tightly structured programs, helmed by organized leadership that is accountable for the GHE’s policies, keeping the program’s eye on long-term sustainability, and the training of individual students.

Adina’s uncle’s doubts about the benefits of GHEs highlight the disconnect between students’ and local perceptions of GHEs and the difficult positions in which both parties may find themselves. Unprofessional behavior by individual students is a problem even when students are screened prior to participating in GHEs [13]. For instance, students may overlook the importance of dressing appropriately or arriving on time at the host institution, partly because they do not consider a global health elective as important as other rotations. Without a responsible GHE program leadership to redirect students, engage Adina’s community, and take responsibility for the implementation-related challenges that Adina, her uncle, and Jessica will confront, conflict will erupt between the students and the community.

Effective Leadership

An effective leadership team, comprising local and partner medical school staff, should identify preceptors whose main responsibility will be to create a practice and educational environment that promotes health care for the local community and facilitates students’ education. Absent adequate leadership, GHEs may not have enough clinical personnel to take on teaching without compromising patient care or enough faculty to responsibly develop, implement, and evaluate the GHE curriculum; misconceptions may form among locals and students about the program. All these issues could be addressed by making dedicated GHE preceptors available.

The program leadership can also create time for teaching by increasing the number of clinicians at the GHE site through various funding sources such as grants or groups that support GHEs, like the Child Family Health Foundation (CFHI). The GHE curriculum should be the result of collaboration between the partner medical school and host health facility. It should address key issues such as practicing medicine in an unfamiliar culture and local health care delivery practices, including standards and preferred management strategies for common medical problems. If the GHE site also serves as a clinical teaching facility for local students, the GHE curriculum should allow interaction among all students; such interactions promote international scholarship and understanding.

Consistent with appropriate clinical teaching, availability of dedicated GHE preceptors ensures appropriate supervision of stud ents. Clinical supervision promotes patient safety and may reduce the unacceptably high infectious hazards to students during electives [14]. Students’ activities during the elective should reflect the values and ethics espoused in their home institutions’ curricula. For instance, students’ clinical activities should be supervised and match their level of training. The apprenticeship model should be followed to assist students in adapting the medical values, attitudes, skills, and knowledge to local challenges and opportunities in the provision of health care.

Preparing Students

Exactly how individual students navigate the ethical dilemmas inherent in their GHEs is not described in the literature, and there is little uniformity in the predeparture education that medical students obtain from their medical schools [8, 9]. Student adherence to the profession’s ethical values of justice, beneficence, and non-maleficence in the practice of medicine may be limited by the meaning of these principles in a different culture and health care system. However, since the primary goal for GHEs is to create a learning experience for the students, and service provision is secondary, demonstrating humility is a useful way to interact in an unfamiliar learning environment. Genuinely attempting to seek common understanding and mutual acceptance between student and host will improve both care and the learning experience. For instance, locals may unjustly view students taking time off to sightsee as an unacceptable luxury considering their dire local situation, or a visiting student may be frustrated by patients’ failure to arrive on time without considering the local public transport situation. Dealing with these differences, without necessarily changing one’s view of them, requires that students remain humble and seek guidance from their preceptors.

Individual students may not appreciate their impact on the health care of the local community; it is essential that they see themselves as part of a long-term commitment by the sponsoring medical school, colleagues, and the GHE site to develop a mutually beneficial relationship. Regular progress reports and ongoing feedback to all the stakeholders at the GHE site can contribute to long-term commitment. Students who organize their own electives can learn how to participate by talking to students who have gone on GHEs or requesting information from medical programs that organize them.

It is in the interest of the medical profession to seek innovative ways to deliver a GHE curriculum that is acceptable to the host community. Addressing the ethical challenges that will arise as more medical students participate in GHEs requires effective leadership that is responsive both to the host community and to student concerns. When the profession fails to achieve collaborative leadership that promotes ethical practices and a better understanding of activities at GHE sites, the students and communities that the profession serves will rightly judge GHEs as harmful, patients may feel taken advantage of, and students may struggle to understand the meaning of their GHEs for their professional development.

References

-

Association of American Medical Colleges. 2006 GQ medical school graduation questionnaire: all schools summary report. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2006.

-

From Medical School to Mission: The Ethics of International Medical Volunteerism. Virtual Mentor. 2006;8(12):797-800. http://virtualmentor.ama-assn.org/2006/12/fred1-0612.html. Accessed February 12, 2009.

-

Bezruchka S. Medical tourism as medical harm to the Third World: Why? For whom? Wilderness Environ Med. 2000;11(2):77-78.

-

Bishop R, Litch JA. Medical tourism can do harm. BMJ. 2000;320(7240):1017.

- Grennan T. A Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing? A Closer Look at Medical Tourism. McMaster University Med J. 2003;1(1):50-54.

- Ramsey KM, Weijer C. Ethics of surgical training in developing countries. World J Surg. 2007;31(11):2067-2069.

-

Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada. Towards a medical education relevant to all: The Case of Global Health in Medical Education. http://www.cfms.org/pictures/file/Global%20Health/The%20Case%20for%20Global%20Health%20in%20Medical%20Education-%20AFMC.pdf. Accessed on February 12, 2010.

- Izadnegahdar R, Correia S, Ohata B, et al. Global health in Canadian medical education: current practices and opportunities. Acad Med. 2008;83(2):192-198.

- Miranda JJ, Yudkin JS, Willmot C. International health electives: Four years of experience. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2005;3(3):133-141.

-

Dowell J, Merrylees N. Electives: isn't it time for a change? Med Educ. 2009;43(2);121-126.

- Haq C, Rothenberg D, Gjerde C, et al. New world views: preparing physicians in training for global health work. Fam Med. 2000;32(8):566-572.

- Banatvala N, Doyal L. Knowing when to say "no" on the student elective. Students going on electives abroad need clinical guidelines. BMJ. 1998;316(7142):1404-1405.

-

Global Health Education Consortium. Professionalism 101: How to be professional and act ethical when abroad. http://globalhealthedu.org/PublicDocs/professionalism_cfhi.pdf. Accessed February 12, 2010.

- Wilkinson D. Medical students, their electives and HIV. BMJ. 1999;318(7177):139-140.