Case

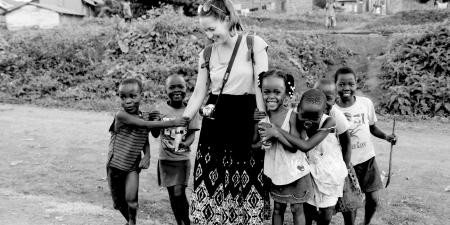

Adina and Jessica are third-year medical students on the same team during their medicine rotation. One day at lunch, Jessica begins to tell Adina about her plans to do a global health elective over their summer break. After a year of clerkships, she is excited to travel to Thailand to see the way medicine works in a developing nation. She thinks going abroad will strengthen her residency application and give her an opportunity to practice clinical procedures and skills that she rarely gets a chance to use in the United States.

Adina, who was born and grew up in Ethiopia, questions Jessica’s decision to spend her summer visiting hospitals abroad. Adina deplored the programs that sent medical trainees into her home village when she was younger. She explains that many local people felt that the foreign students who came to their village for short periods of time actually placed a burden on the health care system rather than contributing to improving care. She tells Jessica about how her uncle, a pediatrician, met several students who rotated through his hospital. They came into the community, lived in a group apart from the people, and barely interacted at all with the local clinicians. When they were in the hospital, they frequently needed a lot of translating assistance to communicate with patients and figure out what resources were locally available in the hospital or the town. Adina’s uncle was also shocked that foreign students were often allowed to take on tasks above their level of training, although this tended to be viewed by the local people as an opportunity to help the students by allowing them to practice their skills. This took up nursing and support staff time, distracted from the education and training of local clinicians, and further stressed an already resource-strapped system.

The visitors also failed to try to understand the local culture. Adina’s uncle had told her, for example, that the visiting students, used to a time- and appointment-driven system in the United States, got very frustrated and even angry when patients did not show up exactly on time or were annoyed when patients’ families accompanied them to visits, a crucial support system in the culture. The superficial working relationship between the local and foreign students and clinicians was weakened further when the visiting students skipped work to travel or sightsee.

Commentary 2

A successful collaboration in global health medicine requires significant planning and commitment. However well-intentioned, a global health rotation without proper forethought can create distrust of the visiting clinicians and their institutions and place unnecessary strain on the local health care system. For American medical students, such a rotation can add important experience to their training, but it needs to be developed in a collaborative fashion that also benefits the local community.

Inherent in the phrase “to practice medicine” is the understanding that physicians are constantly learning—taking in new procedural techniques, medical therapies, and newly discovered causes or manifestations of illness—while striving to provide the best care possible. This occurs at all levels of training, from medical students just starting their education to established, senior attending physicians following the evolution of their chosen fields. Conflict can arise between the need to allow trainees to gain experience and the duty to provide the best care possible to patients. The medical profession has always understood itself to entail lifelong learning; this is encouraged with certification, recertification, and continuing medical education requirements. This same value is imparted to trainees by ensuring adequate supervision, as outlined in the Institute of Medicine report [1], and by incrementally increasing their responsibilities as they advance in their training. These same checks and balances need to be applied to medical student rotations abroad to ensure a safe learning environment for the patient and the trainee. We will first discuss some key elements of trainee supervision and appropriate responsibilities that may be unique to international rotations before turning to a broader view of a successful global health relationship.

Supervision can be a challenge in a resource-limited setting. Improperly supervised medical students encounter unfamiliar illnesses and advanced presentations of disease, with a limited, often unfamiliar, arsenal with which to treat these illnesses. Although it is tempting to think that treatment by an inadequately supervised individual is better than no treatment at all, such an experience can lead to frustration, confusion, and distress in the student and can engender the local population’s distrust. Therefore, a successful medical student global health rotation ensures safety through adequate supervision comparable to that which the students receive at their home institution.

Both the hosting and home institutions should commit to providing more advanced trainees or attending faculty to accept this responsibility. In a resource-limited environment, supervision may still not be sufficiently rigorous during this rotation. Therefore, it is particularly important that the roles and responsibilities of medical students incorporate the norms of their host country but not exceed that which is customary at their home institutions. For example, students who have not yet completed clinical rotations should not be given clinical responsibilities abroad. These students may benefit from shadowing an established local practitioner. It is important to recognize that any inclusion of medical students in clinical settings, as observers or active assistants, requires additional time and responsibility, which may increase the local practitioner’s burden; incorporating foreign students requires time not only to teach clinical medicine but also to perform a sort of cultural and linguistic translation. An experience as an observer, which would be less demanding of the local practitioner, can also be valuable for the student, furthering interest in global health, fostering cross-cultural communication skills, and enabling students to better understand local culture, clinical illnesses, and health concerns.

Adapting to different illnesses and constrained diagnostic and therapeutic interventions in a resource-limited setting can be difficult even for senior practitioners. Medical students who participate in these electives need ongoing supervision and instruction about local diseases, available resources, and approaches to clinical illness. Cultural differences, unfamiliar health beliefs, and language barriers further compound the difficulty of adapting to a new clinical setting. The additional challenges of a resource-limited setting may require a longer time commitment than most clinical electives in the Unites States. Committing additional time to the global health elective will improve the experience for the medical student and foster trust among the local population. Early planning to accommodate global health electives within the framework of required clinical rotations and residency program application will help facilitate longer global health rotations.

Some of the necessary preparation for a successful rotation abroad can begin at home. Although understanding our own biases and beliefs is important for any medical practitioner, it is particularly helpful to become aware of them prior to traveling abroad. Cultural context provides a lens through which we experience events, informed by the specifics of our background: nationality, race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, educational background, religious beliefs, and socioeconomic status. Understanding the nuances of our own cultural bias helps us avoid imposing these biases on others. Medical practitioners should always work to understand the cultural context from which their patients approach illness, striving to respect and understand their patients’ beliefs and preferences with regard to their health and medical care, and to avoid imposing their own biases. International experiences allow both local and visiting practitioners to confront cultural differences and work towards improved cross-cultural understanding. Any traveling medical student should begin to think about his or her own cultural context, as well as learning about the history, culture and language of the host country, prior to leaving for the rotation.

A global health partnership should not only provide a learning opportunity for the medical student but should also meet the needs and goals of the hosting community. Even when educating medical trainees in a clinical setting, the primary emphasis should still be on providing the best clinical care possible. It is important that program leaders focus on:

- understanding the long- and short-term health needs of the community by consulting with community members and leaders—medical, political, and social—thereby increasing community investment in the project;

- establishing long-term goals and putting in place the oversight to create continuous, sustainable projects lasting longer than an individual student’s tenure in the country; and

- training the local health care personnel.

Emphasizing these priorities is crucial to the creation and long-term success of a collaborative global health program.

References

-

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Optimizing Graduate Medical Trainee (Resident) Hours and Work Schedules to Improve Patient Safety, Ulmer C. Residency Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision and Safety. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2009.