Case

State Medical University is working to design and implement an updated version of its curriculum. As part of this new curriculum, the university would like to establish a policy for student engagement in the community. The dean, Dr. Grant, suggests that students need to be active in serving the larger community in which they live and study during their medical training. He emphasizes that this would be an excellent learning experience for the students, inasmuch as he views the urban community where the university is located as a different world from that which the majority of the medical students have previously experienced. Several other faculty members agree with Dr. Grant’s opinion.

Ramona, the medical student representative to the committee, agrees that that many of her classmates entered medical school wanting to make a difference and improve the lives of others. She suggests to the committee that both local and international experiences could enhance the new curriculum and students’ education. She is intrigued by the opportunity to visit a foreign country for an elective. She suggests to the committee that prospective students look for global health experiences when choosing a medical school. She stresses that she believes that experiences in developing nations provide unique educational opportunities that students cannot get in their local surroundings.

Several of the faculty members express concern over the idea of the university’s devoting resources to international electives. They suggest implementing a policy which would not permit students to go on international rotations for academic credit, preferring that they work to address the local need that surrounds them.

Commentary 1

Suffering, loss, and death are part of the human condition, but physicians today have more knowledge and capacity to address suffering than ever before in history. Accelerated travel and instant access to information make the world feel smaller. Images and stories of the billions of people living in poverty in low-resource settings reveal stark evidence of health and economic disparities. While human suffering has always been present, today we are constantly reminded of the gaps between what we know and what we do. Physicians and health professionals are called to respond to the needs of millions at home and abroad who lack access to basic health care.

The duty to serve those in need despite their economic circumstances and to practice beneficence are foundational principles of medical ethics, but health care needs will always exceed an individual physician’s resources. Therefore physicians are challenged to weigh external needs against available resources and their own life circumstances in deciding when and where to serve.

Since medical students are engaged in an intensive education program, their time for elective service is limited, even though working with disadvantaged populations, whether domestic or international, can be an important part of medical education. Through such experience, students can confirm their motivations and build confidence and skills that will be used throughout their careers. Medical students who feel called to serve those in need, however, may be overwhelmed, intimidated, and confused about where and when to begin. How does a student discern the best opportunity for service to the disadvantaged among so many options?

There are many reasons to pursue local service to disadvantaged populations, including proximity, familiarity, and social accountability. Medical schools are best prepared to help local communities due to their proximity, their familiarity with the culture and local conditions, and access to local and regional resources and networks. Medical schools and academic health centers receive numerous benefits from local and regional communities, including income and a steady supply of patients and employees. Without patients from local communities, medical schools would not be able to perform their essential functions—patient care, research, and education. Moreover, medical institutions that are genuinely concerned about societal health cannot ignore problems in their own backyards. Working with local disadvantaged populations helps fulfill a university’s ethical obligation to the community in which it resides [1, 2], while promoting a spirit of service, furthering students’ skills and confidence in their ability to work with underserved populations, and often sparking interest in additional service both at home and abroad.

The individual student may also have compelling reasons for choosing a local over an international rotation. Students with budget restraints or family needs may find it impossible to study abroad. Residency programs may or may not provide opportunities for global health experience. Local opportunities are more efficient for students, due to low travel time, affordable cost, and easy access throughout the course of their medical training. They are often more closely supervised by faculty and more likely to be sustained and evaluated to assess impact. If we understand that global health concepts transcend borders, and that determinants of health are frequently rooted in socioeconomic conditions, students can gain global health skills by working with medically underserved populations in our own nation.

Given the need in local disadvantaged populations and the advantages for students of volunteering at home, why should U.S. medical students or faculty consider service abroad?

Increases in international travel, trade, and immigration have resulted in more than 1 billion people crossing international borders annually and have enhanced global interdependence for health. Concurrently, U.S. society has become a mosaic of diverse cultures, languages, and health values. Never has it been more important for future health care professionals to understand and experience health in a global context. These factors have contributed to the growing interests of U.S. medical students in global health; the number of U.S. medical students participating in overseas electives increased from 6.4 percent in 1984 to 29.9 percent in 2009 [3]. Restrictive university policies toward international experiences could deter a certain subset of students from enrolling; such policies also send an implicit message that the university does not value or place importance on global health. Many U.S. medical schools are now scrambling to address students’ increased interests in service opportunities, grappling with how to prepare students and evaluate these experiences and determining how to balance local and global needs in the context of finite resources.

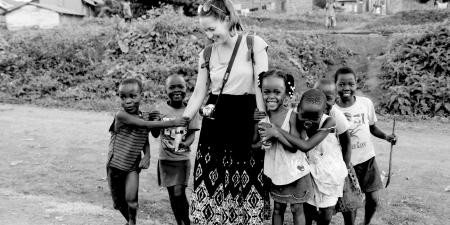

Research on the impact of global health experience demonstrates numerous benefits, including increased knowledge, changes in attitudes, and enhanced medical skills. Despite the ubiquity of electronic and printed information, there is no substitute for living and working in low-resource settings. There is no replacement for hearing the cries of a mother who has lost her child from a preventable illness or for being present at the bedside of a person who has died in pain. Such experiences leave indelible impressions on the psyches of physicians-in-training that can inspire a lifetime of service. These experiences often have lasting effects on the attitudes and career choices of participants, regardless of whether they plan to work in the U.S. or abroad. Participants recognize that skills in cultural understanding, community health outreach, patient education, illness prevention, interdisciplinary teamwork, and communication are necessary for the practice of medicine in any location [4, 5].

While students may gain these skills through global health experiences, however, they can also be acquired in culturally diverse and impoverished urban or rural regions of the U.S. Therefore, students should be permitted to go on international rotations for academic credit and should be encouraged or required to engage in local service learning opportunities. Serving populations abroad, if not balanced with local service, signals a lack of accountability to local populations. Conversely, exclusive service to local populations indicates parochialism and diminishes our ability to address extreme health disparities abroad. These experiences are mutually reinforcing, provide opportunities for sustained services to medically underserved populations, and reflect the social accountability of the institution to address local needs. Service, whether local or global, is based on the principles of equity and access to health care as a fundamental human right; both are manifestations of compassion and concern for the worth and dignity of all.

University policies that are explicitly or implicitly restrictive of service opportunities will limit students’ exposure to working with underserved populations, as well as their ability to discover the value and rewards of such work. Commitment to the medically underserved is a driving force in some students’ decision to apply to medical school. Official university endorsement of service learning will help these students feel at home, may encourage them to further their service experience—perhaps taking on leadership roles—and may protect them from the disillusionment many altruistic students experience after entering medical school. U.S. medical school faculty need to respond to the call for increased global health education, being mindful of resource constraints while also serving local health care needs. Cross-cultural and global health training opportunities should be designed and evaluated to ensure that they meet educational goals and are available to all students in U.S. medical schools.

Although early exposure is necessary, it is not sufficient to attract and retain adequate numbers of health professionals to work in medically underserved areas. There are severe current and projected shortages of health professionals willing to serve disadvantaged populations in the U.S. and abroad [6]. Recruitment, good working conditions, and support to retain these physicians and their families will be necessary to ensure sufficient numbers of health professionals distributed according to the needs of populations. Addressing global health needs will require advocacy, training, recruitment, appropriate distribution, and solidarity among a global workforce of health professionals [7].

Wherever it occurs, experience with low-resource, cross-cultural settings can change the course of a physician’s career. The lessons that can be learned from caring for disadvantaged patients and communities in domestic and foreign locations are too valuable to be missed. There will be countless opportunities for medical students and physicians to serve disadvantaged communities throughout the course of their careers, but they must be sufficiently experienced, prepared and willing to take them. Socially accountable medical schools should support opportunities for students’ learning and service in low-resource settings both at home and abroad.

References

- Woollard RF. Caring for a common future: medical schools’ social accountability. Med Educ. 2006;40(4):301-313.

-

Boelen C, Heck J. Defining and measuring the social accountability of medical schools. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1995. (Unpublished document WHO/HRH/95.7.)

-

Association of American Medical Colleges. 2009 GQ medical school graduation questionnaire: all schools summary report. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2009. http://www.aamc.org/data/gq/allschoolsreports/gqfinalreport_2009.pdf. Accessed on January 25, 2010.

- Haq C, Rothenberg D, Gjerde C, et al. New world views: preparing physicians in training for global health work. Fam Med. 2000;32(8):566-572.

- Ramsey A, Haq C, Gjerde C, Rothenberg D. Career influence of an international health experience during medical school. Fam Med. 2004;36(6):412-416.

-

Joint Learning Initiative. Human Resources for Health: Overcoming the Crisis. Cambridge, MA: President and Fellows of Harvard College; 2004.

-

World Health Organization. Global Health Workforce Alliance: About the Alliance. Geneva: http://www.who.int/workforcealliance/about/en/. Accessed January 25, 2010.